Inside the World of the Digo People in Coastal Kenya

By the time the first light breaks across Diani Beach in Kenya, the Indian Ocean is already a shimmering expanse of turquoise. Tourists sip their morning coffee, unaware that just beyond the white sand and swaying palms lies a world as old as the tides themselves. Here, if you walk inland—away from the surf and the resorts—you enter the realm of the Digo people, a coastal tribe whose quiet resilience and deep-rooted traditions remain largely unknown to the outside world.

Africa, in all its vastness, is a continent that rewards the curious. Guidebooks may warn against venturing too far from the well-trodden path, but the real stories, the ones that linger long after your footprints have vanished, begin where the pavement ends.

It was on Diani’s outskirts that I met Matokeo—a Digo man with a ready smile and a storyteller’s heart, who now runs a humble beachside restaurant. Sensing my eagerness to learn, he offered an invitation that would become the highlight of my journey: a walk to his village, deep in the savannah beyond the tourist gaze.

The next morning dawned with a gentle rain—nature’s blessing for our 40-minute trek through fields of whispering grass. Along the way, we were joined by Matokeo’s sister, a seafood vendor from nearby Ukunda. Her laughter mingled with the patter of raindrops as Matokeo recounted tales of his childhood: how he learned the secrets of the land from the village’s medicine woman, and how the Digo, with their intimate knowledge of nature, find sustenance and healing in the world around them.

For generations, the Digo have been custodians of the Kaya—sacred groves recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites. Traditionally, each Digo clan had its own kaya, a fortified settlement hidden within the forest, serving both as a spiritual center and a refuge in times of conflict. Even today, rituals and community decisions are often made beneath the ancient trees, and elders act as the guardians of these sacred spaces.

The Digo are one of the nine ethnic groups collectively known as the Mijikenda, who inhabit the coastal region of Kenya and northern Tanzania. Numbering around 350,000, the Digo have traditionally lived in small villages, their lives closely intertwined with the forests and savannahs that stretch inland from the sea. Their language, Chidigo, is a Bantu tongue distinct from Swahili, though most Digo are multilingual.

As we walked, Matokeo paused beside a nondescript bush. With practiced hands, he gathered a handful of leaves, crushed them in water, and conjured a frothy lather—the Digo’s natural soap, used for generations. It was a simple act, but one that spoke volumes about a way of life attuned to the rhythms of the earth.

The narrow path beneath our feet had been worn smooth by countless Digo before us. Every tree, every leaf, every birdcall had a purpose, a story. I realized, with a pang of humility, how little I truly understood about the natural world.

We passed the crumbling remains of Matokeo’s primary school. “I walked barefoot every day through the bush, rain or shine,” he recalled, pride lighting his face. Education, here, is not a given—it is a hard-won treasure.

Friday is market day. The air buzzed with life as Digo traders hawked everything from vivid kitenge fabrics to fragrant street food and counterfeit football jerseys. The market’s chaos faded as we reached the last village before Ukunda—a place Matokeo once called home. Orphaned young, he was raised by a woman he calls “mother,” who now cooks for the village’s parentless children, her generosity as boundless as the sky above.

Nearby, an elderly woman dozed on a wooden bench outside her mud-walled house. At 102, she is the matriarch, the living root from which the village branches. In a society often mischaracterized as patriarchal, she is the undisputed decision-maker, her wisdom shaping the lives of all around her. Draped in a handwoven purple throw, she agreed to a photograph—her dignity undiminished by age or tradition.

While the majority of Digo today identify as Muslim—a legacy of centuries of contact with Arab traders—many ancient beliefs endure. Animism, ancestor veneration, and the role of the “mganga” (traditional healer) remain woven into daily life. The Digo’s syncretic faith, sometimes called “folk Islam,” is evident in rituals that combine Quranic verses with offerings to ancestral spirits.

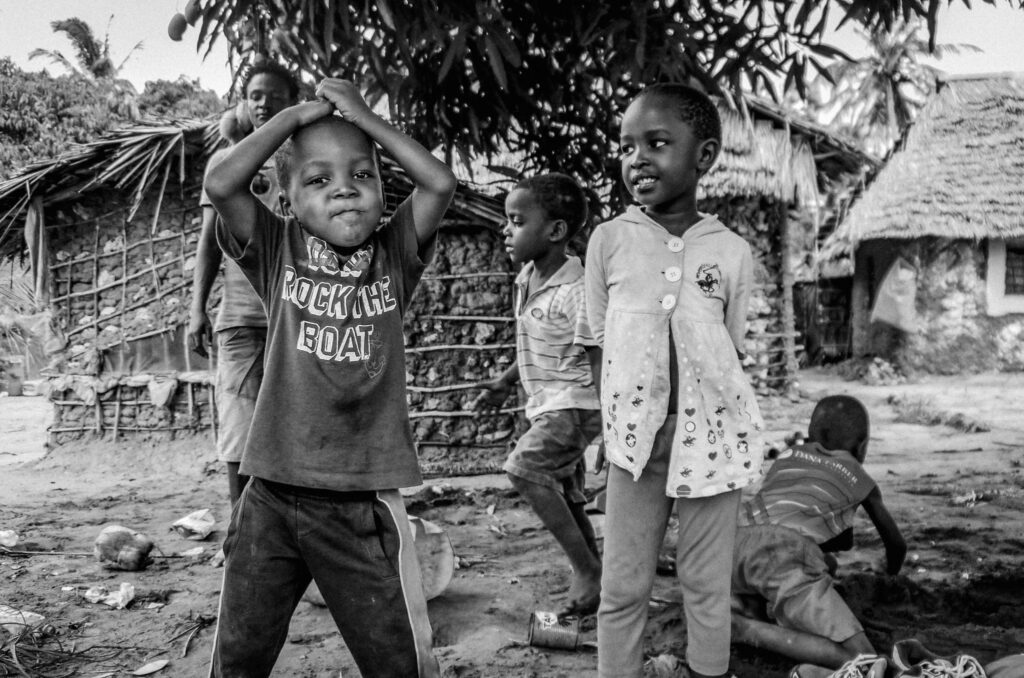

Children gathered around me, eyes wide with curiosity. One girl reached out to touch my arm, as if to confirm I was real. For many, a visitor from afar is a rare and wondrous sight. Their play was resourceful and unbridled—homemade toys from tinfoil, tree-climbing races, and the sweet reward of fresh coconut juice, brought down by Matokeo himself after scaling a towering palm.

Digo society is built on a foundation of communal support. Extended families share resources, and elders command deep respect. Women, though often described as having little “political” power, are frequently the heart of the household and, as I saw, sometimes the village itself.

In the heart of the village, laughter spilled from a small hut where men and women draped in kitenge—vivid, patterned cotton cloths that are as much a statement of identity as they are a practical garment, shared coconut wine, their voices rising above the absence of music. I was welcomed with a wooden stool and a glass of the potent, milky drink—a taste of Digo hospitality, unfiltered and unforgettable.

Travel has taught me that the richest stories often lie far from the guidebook’s pages. The Digo, with their quiet strength and deep connection to the land, reminded me that the extraordinary is often hidden within the ordinary. These moments—shared meals, exchanged smiles, lessons learned under the African sky—are the true treasures of the road.

As I left the village, I knew I carried with me more than memories. I carried the stories of a people whose lives, though rarely chronicled, are as vibrant and enduring as the land they call home.