Journey to the Heart of the Maasai (Post-Trip Impressions)

My legs were numb as the jeep veered off the last stretch of tarmac and onto a faint track, the kind that only exists in memory and the occasional tire rut. The road, if it could be called that, unraveled into the wild Tanzanian bush, where impalas flashed across the savanna in bursts of cinnamon and white.

I was bound for a remote Maasai village—a speck on the map, deep in the heart of nowhere. The chance to visit such an authentic community felt like a rare gift, a highlight of my life that would have been impossible without the right connections. As the landscape grew wilder, I felt a surge of gratitude for the path that brought me here.

After two hours of bouncing over red earth, we arrived. The village was a cluster of life: a handful of shops, each selling nearly identical wares, a modest church, a schoolhouse. My home for the week was the “grandest” in sight—a concrete house, arranged by my hosts, with no guesthouses for miles around. Even here, luxury was relative: no shower, only a bucket and a trickle of water; the toilet, a simple hole in the ground inside a mud-walled hut.

Electricity was a fragile promise, delivered by a solar panel too weak to charge my laptop, with my phone gasping at 15% after hours plugged in. It was the perfect opportunity to disconnect, to let the bush swallow my worries and my to-do lists.

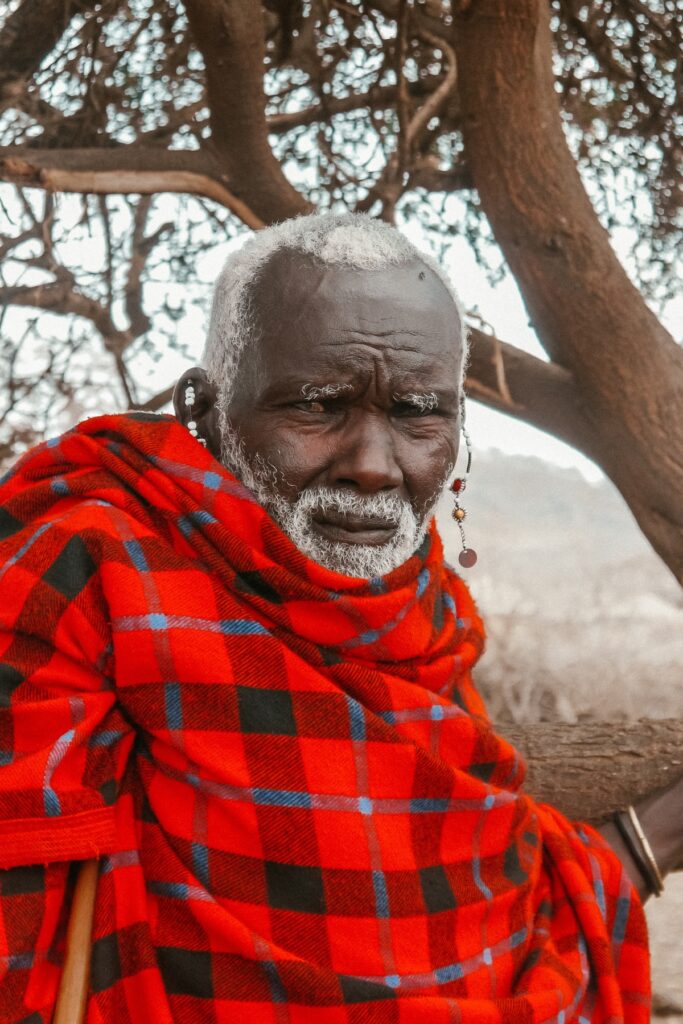

If you’ve ever traveled northern Tanzania or southern Kenya, you’ve seen Maasai men: tall, wrapped in brilliant shúkà cloth, guiding cattle along the roadside. They seemed mythic to me as a child in geography class—majestic, powerful. To meet them now, to ask questions and share stories, felt like stepping into a legend.

Africa is so often misunderstood. The media’s lens lingers on hardship—starvation, conflict, thirst. While these realities exist, they are not the whole story. Africa is vast, and its truths are many. Even here, where the Maasai face real challenges, the narrative is richer than pity.

Water, for example, is a daily trial. In the rainy season, a great river swells nearby—though “nearby” means a four-kilometer trek. During my visit, the riverbed was bone-dry. So the women, as tradition dictates, set out before dawn, walking ten kilometers with their donkeys to the nearest borehole. There, laughter and gossip ripple among the women as they fill buckets, balancing them atop their animals for the long journey home.

Meanwhile, the men tend the cattle. I joined them on a ten-kilometer hike to the forest, where the river once flowed. There, Maasai men dug deep into the earth, coaxing water from hidden springs for their herds. Two of these men, I learned, held university degrees. They worked in town but returned whenever possible, drawn by the slow rhythm of village life. I watched as one paused his labor to snap a selfie with his Samsung Galaxy—a reminder that tradition and modernity walk side by side here.

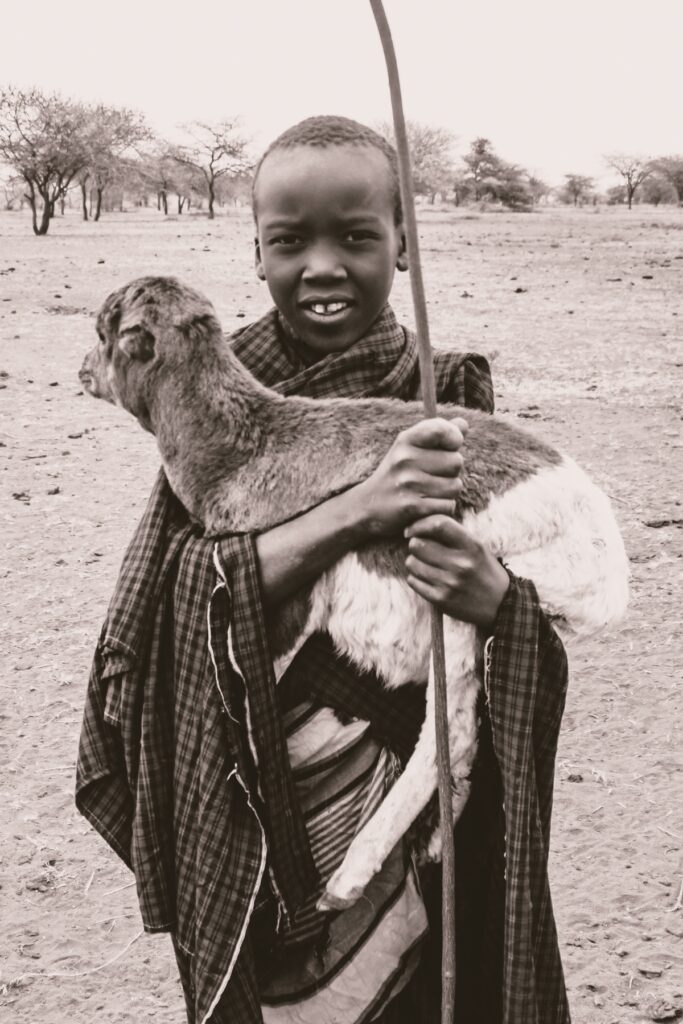

The Maasai’s devotion to their animals is astonishing. Men and boys—some as young as five—spend twelve hours a day grazing livestock. I watched two children, barely taller than the goats they herded, guide a flock of over five hundred, aided only by a scrappy dog. When one stubborn kid refused to walk, a boy scooped it up and carried it, determined and gentle.

Each day, I wandered the bush—sometimes for work, sometimes in pursuit of wildlife, sometimes simply to prepare for my upcoming trek up Mount Nyiragongo. Impalas and ostriches darted through the grass. Once, a tower of giraffes materialized, silent and unbothered by my presence.

Every encounter with the Maasai was marked by warmth and curiosity. Children ran to greet me, bowing their heads in respect; I learned to return the gesture, touching their crowns. Women offered me their handmade jewelry, expecting nothing in return. The men shared stories of encounters with lions and cheetahs—predators drawn to their livestock, sometimes fought off with nothing but courage and a spear.

Predator attacks are a fact of life. One afternoon, my guide Kinaru pointed to a tree by the river: “I was grazing goats here when a leopard killed two of them,” he said. Yet, even in the face of danger, the Maasai’s resilience shines. Warriors, dressed in red—the color feared by lions—patrol the bush, knives at their sides. Kinaru assured me that lions rarely attack humans; they have learned to fear the Maasai more than the Maasai fear them.

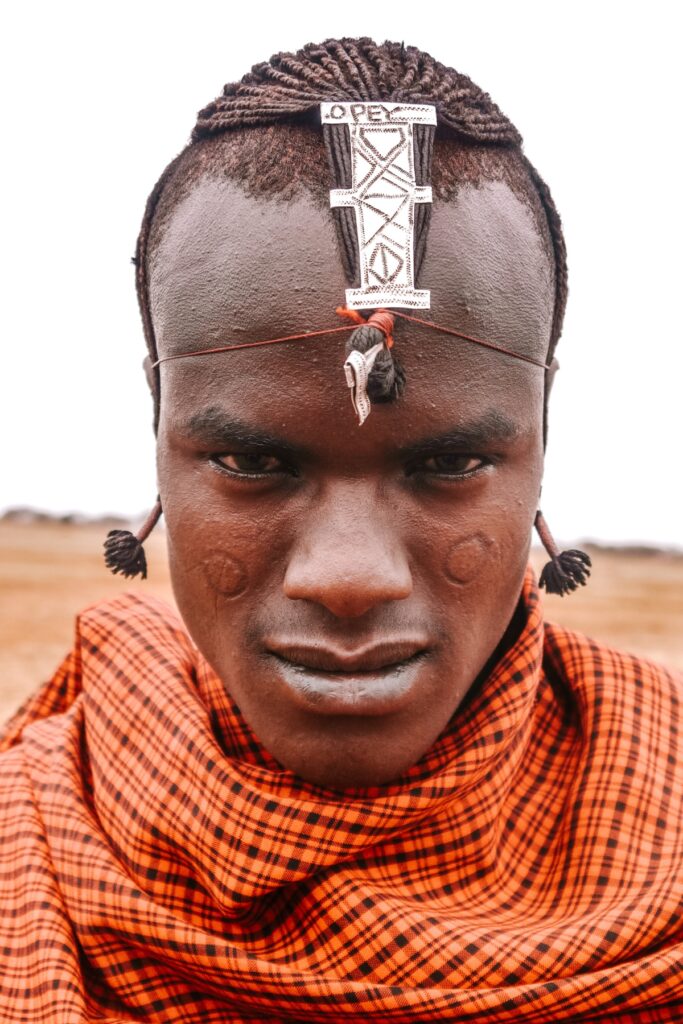

Meeting a Maasai warrior was a moment of quiet awe. I spotted him on the savanna, walking with the measured grace of someone accustomed to wide horizons. He spoke little English, but allowed me to photograph him—a silent exchange, heavy with meaning.

Becoming a warrior is a rite of passage for every Maasai boy. It begins with a circumcision ceremony, a test of bravery endured in silence. For a month, the initiates dress in black, healing. Then, they take up the spear, charged with protecting the community and leading cattle to distant pastures during the dry season. Though the government now requires the Maasai to settle permanently, the men still roam with their herds, honoring a tradition of mobility and stewardship.

My time in the village restored my faith in Tanzania. My first visit, months earlier, left me disillusioned—overcharged, mistrusted, seen as little more than a source of money. Here, I discovered another side: a place where joy is communal, where stories flow as freely as laughter, where strangers are welcomed with open arms.

Every moment was a highlight, but the memory that lingers is of the warrior on the savanna, the sun setting behind him, the bush alive with possibility—a reminder that the world is vast, and its stories are waiting to be told.